Our headline dates (1780-1925) are far from being the whole story when it comes to thinking about data collection and record linkage. One of our stated objectives in our original application elaborates:

to chart the fortunes of all Londoners convicted at the Old Bailey between the departure of the First Fleet to Australia (1787) through to the death of the last transported Londoner in Australia in the early 1920s

But in order to do this, we need to look at data from significantly earlier than 1787, or even 1780. Our interest in convicts doesn’t start at the moment of the Old Bailey trial that sent them on their journeys to Australia. For 18th-century offenders, we don’t have census or civil registration records that we can use, so our focus will be on attempting to trace earliest contacts with the criminal justice system. But if we go too far back, we’ll spend a lot of time and computing resources processing data we don’t need, which will increase problems with noise and false positives (especially when we’re looking for needles in haystacks of unstructured data like newspaper or sessions papers).

Still, it seemed worth checking a more simple question initially. We knew some of the convicts transported in 1787 would have been held in the hulks for several years, as authorities sought a replacement for the American colonies (those pesky Revolutionaries). How long exactly? We wanted to pin down a more precise date than 1780.

The First Fleet entering Port Jackson, January 26, 1788 (State Library of New South Wales)

The Old Bailey Online isn’t a very useful source for this question, however convenient it might be (a few moments with the stats search tells me, for example, that 1258 people were sentenced to transportation between 1781 and 1786), because sentences given after trials don’t necessarily reflect actual outcomes: not everyone who was sentenced to transportation was actually transported; and not everyone who was transported had been given that sentence in court (a significant proportion of of death sentences was subsequently commuted to transportation). In addition,between the collapse of transportation to the American colonies and the establishment of Australia as the primary recipient of transported convicts, there were experiments with transportation to other colonies.

I needed different sources, based on the actual transportation records, so it was a chance for me to start learning about the transportation and Australian datasets I’m not familiar with. In fact, there is plenty of source material: many of the transportation records routinely included information about the convicts’ trials – offence, court, and date convicted. Moreover, a number of projects have already produced readily usable and accessible datasets based on these sources.

I started with the State Library of Queensland British Convict Transportation Registers database (BCTR), created from Home Office registers (TNA HO11, for those who’re interested). We’ve already indexed this data in Connected Histories. The CH version wasn’t designed for this kind of data analysis, however, and to run individual searches would have been a long slow job, so I downloaded the full dataset and played with it (using OpenRefine) until I got the information I wanted. The earliest trial in there, it seemed, was that of John Martin, in July 1782.

The second relevant and easily accessible dataset was the First Fleet database (FF-DB), which is also available to download. This is a smaller dataset, containing the 780 or so convicts transported on the First Fleet, of whom 327 had been sentenced at the Old Bailey. Unlike the BCTR, it’s been compiled from a number of different primary and secondary sources. In FF-DB, the earliest Old Bailey trials were from 1781. The earliest trial of all was that of Samuel Woodham and John Ruglass, at the sessions of 30 May 1781.

Why hadn’t I found these in BCTR? Because, it transpired on reading the entries, in each case their journey to Australia was actually their second convict voyage. They’d escaped from their first convict destination and had been convicted of returning from transportation around 1784-5. BCTR only gave the date of the second conviction that actually put them on the ships to Australia, whereas FF-DB records both. Most of the 14 FF-DB convicts from 1782 trials had also returned from transportation (several had been involved in the Mercury mutiny) and been re-sentenced at a later date.

Don’t ya just love the way a ‘simple’ historical question is never so simple after all?

A different question I decided to ask the data: setting aside 1781-2 outliers, what was the more normal interval between conviction and departure for Australia for the Old Bailey First Fleeters? The following table is taken from the FF data (without taking the “re”-transported into account): 213 (65%) were originally tried in 1784 or earlier. Those who’d spent less than 3 years in the hulks could presumably consider themselves the lucky ones.

| Year of conviction |

Number of convictions |

| 1781 |

4 |

| 1782 |

14 |

| 1783 |

48 |

| 1784 |

147 |

| 1785 |

37 |

| 1786 |

49 |

| 1787 |

28 |

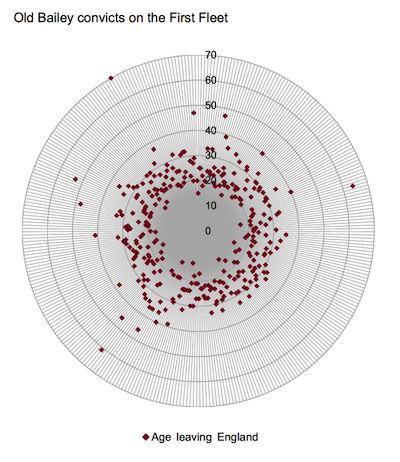

Now I needed to investigate the age range of the First Fleet convicts, which would help me to work out the likely earliest dates of contact with the justice system. Both the transportation and Old Bailey Online data contain at least some information about ages, although 18th-century information on this is often imprecise and not always accurate. I wasn’t too worried about this, since they didn’t need to be exact for this purpose.

What are the recorded ages of the First Fleet convicts in FF-DB? There is age information for 309 out of the OB sample of 327 (bearing in mind these are recorded as ages at the time of departure, so they’d have generally been a few years younger at the time of trial). I think it will hardly come as a major surprise to 18th-century crime historians that the majority (64%) were between 20 and 30 years old, and the vast majority (95%) were over 15 and under 40.

That age data could be skewed in various ways, though: it’s conceivable that those selecting prisoners for the First Fleet tended to choose younger people who’d be more likely to survive the passage, and be stronger workers at the other end; on the other hand, though, we might reasonably speculate that very young offenders would be less likely to be transported.

Age data is available for only about 3% of Old Bailey Online defendants between 1740 and 1780 (contrasting sharply with the later 19th-century Proceedings – which in itself tells us a lot about changes in record-keeping generally and surveillance of the criminal elements in society in particular). We have no idea how representative that 3% was so I’m wary of taking any hard numbers from it. (And again, I can imagine that very young offenders might be slightly less likely to appear at the Old Bailey than at lower courts.) But it does show a reasonably similar profile to FF-DB, with very, very few defendants under 15, though rather more between 40 and 50 – which might (if we could really trust it) back up my notion that the First Fleet convicts tended to be selected from younger prisoners.

Using the age of 45 (in 1787) as an upper limit would give a birth year c. 1742 – let’s round that down to 1740 for convenience. So, if they were unlikely to appear in criminal justice records much before the age of 15, that takes us to 1755. That too will not be quite the final word: we’ll probably do manual searches in earlier records for the handful of First Fleeters aged over 45, and for individuals who appear to have exceptionally rich stories. But in terms of data collection for automated searching/processing, that is likely to be close to our “real” starting date.