Bob Shoemakers’ keynote address from the Penal History in a Digital Age conference in Tasmania, June 2016, focused on the project’s Epistemologies research theme. He asked: Why did they keep such detailed records about criminals?

What makes the Digital Panopticon project possible is the fact that in nineteenth-century Britain and Australia detailed records were kept for the first time about the personal characteristics of convicted criminals. This information, particularly ages, makes the sophisticated record linkage possible which allows us to compile such substantial life archives for so many convicts.

This was not always the case. In the eighteenth century, and earlier, we very rarely know anything more about convicts than their names and offences; the one exception is convicts who were executed, whose lives were written up in the wonderfully rich, but religiously framed, Ordinary of Newgate’s Accounts

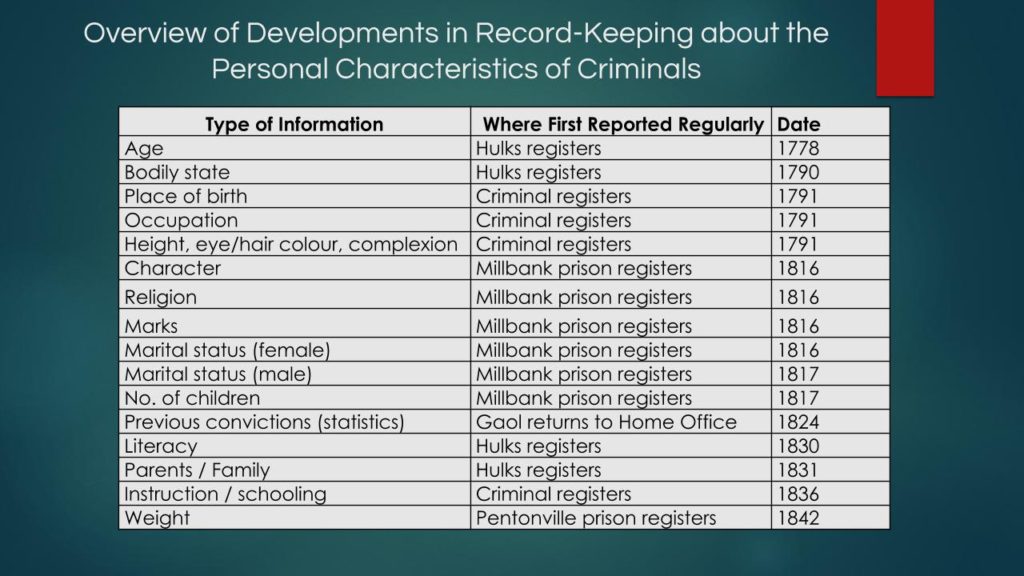

In contrast, records containing personal information about convicts proliferated after 1780. By 1860 a vast amount of personal data was collected: in addition to their names, offences, verdicts, and sentences, details were recorded about ages, places of birth, occupations, marital status, number of children, and parentage; descriptions of their physical appearance (height, weight, eye and hair colour, ‘build’, marks, and tattoos); whether they could read and write, their education, religion; and previous convictions, character, and behaviour in prison.

Overview of developments in record keeping about criminals, 1778-1842

The table provides a brief overview of changes in record-keeping between 1780 and 1860. It can be summarised in three main stages:

The first major innovations, in the late eighteenth century, were the recording of ages in the registers of the hulks (following the introduction of this punishment after the cessation of transportation to the American colonies), and the creation of the criminal registers in 1791 by the sheriffs of London and Middlesex.

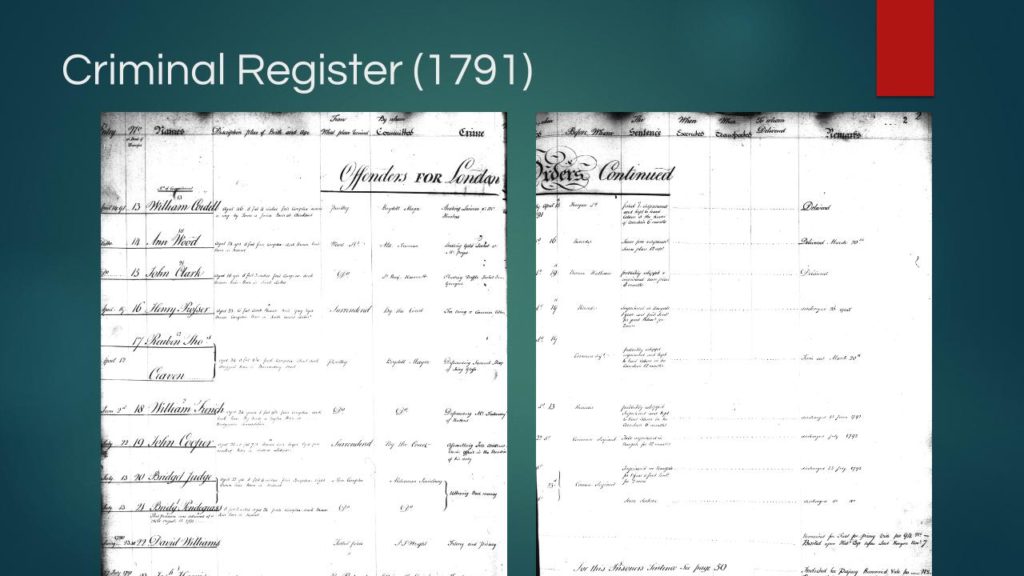

Home Office Criminal Register, 1791 (HO 26)

The criminal registers recorded, largely in tabular form, information about the ages, places of birth, occupations, and physical descriptions for each person accused of a crime and committed to Newgate Prison.

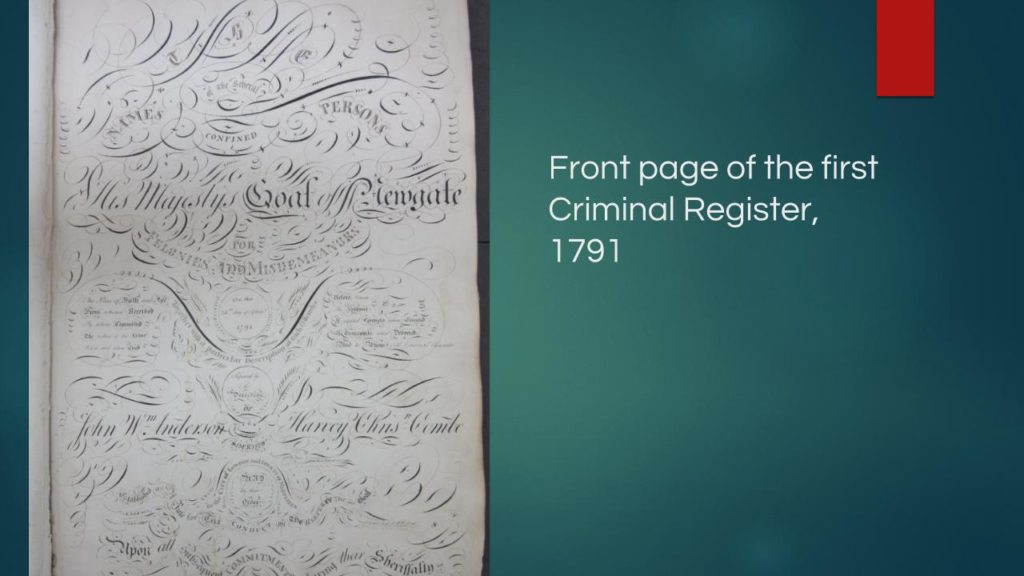

Lavishly embellished front page of 1791 Criminal Register

The elaborate title page in florid handwriting, which proudly promised ‘a particular description of each offender’, indicates the pride taken by the clerk in its creation.

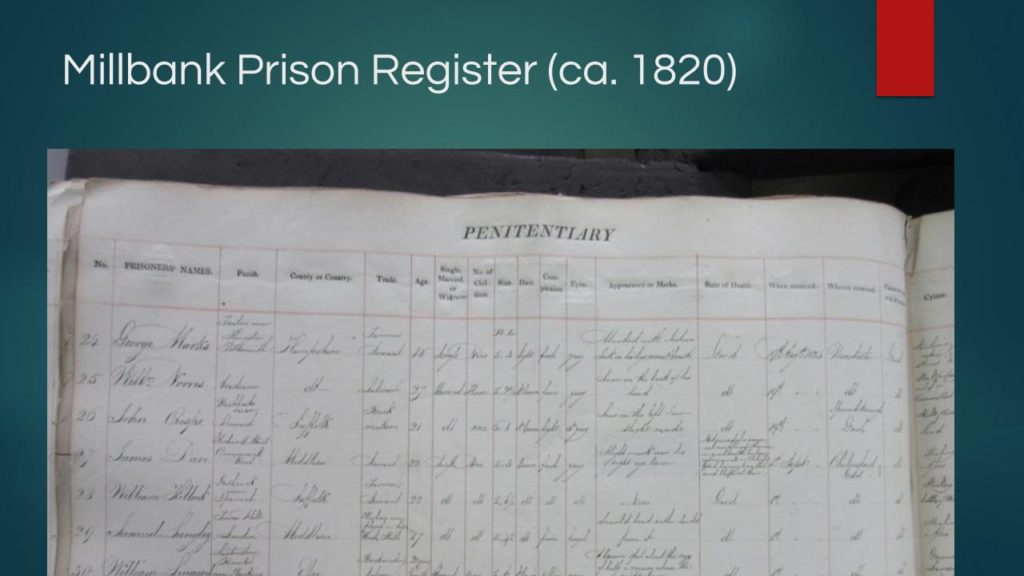

The second stage came with the opening of the first national penitentiary, Millbank Prison, in 1816, whose registers also included information about prisoners’ mental state (their character, behaviour, and religion) and family circumstances (marital status for both sexes, number of children for female prisoners).

Millbank Prison Register, c.1820

The third stage, in the 1830s and 1840s, saw important new developments in existing record series and the development of new record keeping practices by prison chaplains. Information was collected about education (literacy skills and degree of previous instruction, particularly in prison chaplain records), and family and friends, and, in the registers of the newly built Pentonville Prison, prisoner weights.

Why did these changes occur? Scholars have offered various theoretical perspectives. These innovations can be seen as an aspect of the evolution and growth in power of the modern nation state; as part of a society-wide cultural/political initiative to obtain knowledge as a form of control; or as part of growing cultural importance given to ‘facts’. While all these explanations are relevant, we would like to offer a fourth, more crime-focused, reason: that this information collection was the result of a growing desire to understand the criminal. Before developing this argument, what are the limitations of the alternative explanations?

Record-keeping as part of the evolution of the modern nation state works well for Australia, which was run as a military colony for the first few decades (essentially as a prison without walls), so the ‘state’ could easily claim near-absolute power. But in England a focus on the growing power of the state at a national level, on Parliament and the Home Office, doesn’t explain why so many of the innovations in the collection of information occurred at the local level, by local officials, quasi-officials, and independent social investigators such as Henry Mayhew. The criminal registers, for example, were invented by the sheriffs of London.

And while the creation of the Millbank prison registers was dictated by the statute which authorised the building of the prison, the Rules and Regulations for the prison established by the prison committee mandated the collection of additional information, and the actual registers kept by prison officers went even further. If anything, this story is about a growth in local state power, not national power, and even then it was often not formally sanctioned by local leaders.

Under the 1823 Gaol Act, prison chaplains were required to produce an annual written ‘statement’ on the condition of the prisoners under their charge and, from 1840, national prison regulations required them to keep a ‘character book’. There is no evidence that these records were expected to be detailed. However, in their efforts to reform prisoners (and facilitated by the requirement that they visit prisoners on a regular basis), some chaplains went far beyond these requirements and collected extensive qualitative and quantitative evidence.

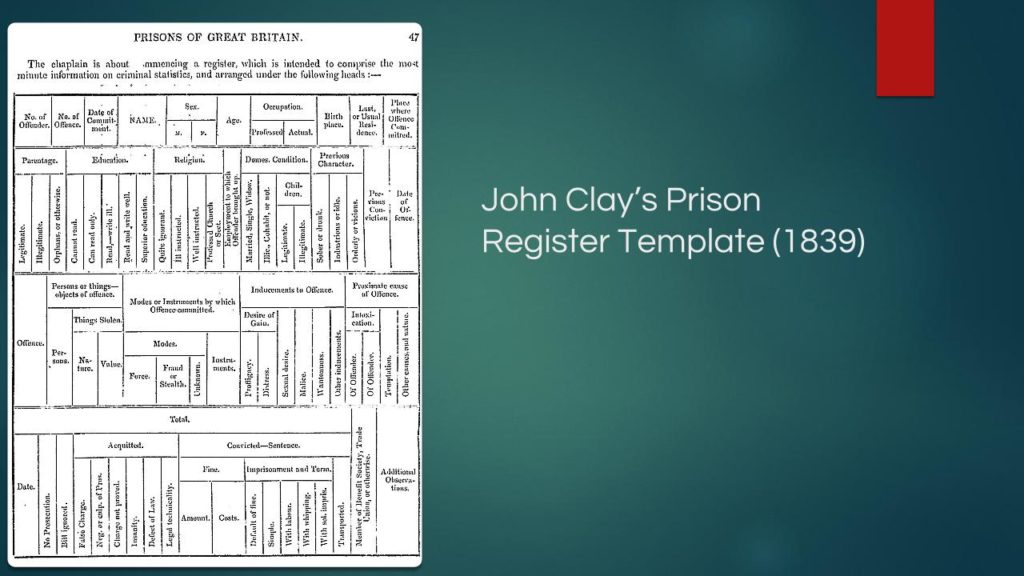

John Clay’s Prison Register Template

John Clay, chaplain to the Preston House of Correction adopted a set of registers in 1839 for recording a vast range of information about those committed to the jail. Although he was the apotheosis of information-gathering chaplains, Clay was not alone: at least twenty other chaplains between 1820 and 1860 also produced detailed reports on their prisoners.

These information gathering activities by local officials were not always welcomed by their superiors. While some local magistrates and central government officials applauded them, others raised objections, and some reports were even suppressed. So, this doesn’t look like a straightforward example of the growth of national state power.

One could instead see the growth of record keeping as a wider phenomenon, perhaps a society-wide development, in which there was a coming together of local and national institutions to obtain knowledge about the governed, as a means of shaping their conduct. This is clearly a significant part of the story, particularly in the context of the apparent increasing ungovernability of society from the late 18th century, in the wake of riot, revolution, and rising rates of crime, but the wide range of individuals involved and scale of the information collected makes it difficult to describe this phenomenon solely as a political exercise.

Moreover, we should not exaggerate either the desire of the state to collect this information, or the amount of power this information gave to those in authority. In a perverse way the collection of this information gave some agency to the accused and the criminal, since they were often the only persons in the room who knew their ages, places of birth, occupations, and religion. At least some prisoners enjoyed their own form of power, reinventing aspects of their identity to, for example, avoid harsher punishments for those with previous convictions or secure more comfortable prison conditions. In 1856 the Governor of Cold Bath Fields prison complained about the large number of convicts who entered his prison with the surname of Smith, thereby creating new identities for themselves so that their previous convictions would not be noticed.

If a political explanation doesn’t work, perhaps we can adopt a more culturally focused one. Bearing in mind that increasing amounts of information were collected at this time about a wider range of issues than just crime and disorder, we could see innovations in record keeping as a result of the growing weight placed on facts, and statistics based on those ‘facts’, throughout society at this time. As anyone who has spent time in British archives knows, the collection of information on a wide range of topics did expand dramatically at this time, but this doesn’t explain why criminals were some of the first subjects of these new record-keeping practices, alongside two other groups: military recruits and aliens.

So these existing explanations don’t fully explain the how, when and what of the increasing collection of personal information about criminals. Our explanation is this: these changes were the result of a new moral and empirically-driven desire to better understand the criminal and the causes of crime (and not just control or punish him).

There were, of course, some more mundane and practical reasons why information about criminals was collected: to assist in arresting suspects and apprehending escapees from prisons, and to assist those responsible for reaching sentencing and pardoning decisions, and determining penal regimes for those committed to prison. But even if we accept that these explanations have some purchase, they do not apply to many types of information collected, nor do they explain why such information was not collected earlier.

Instead, this record-keeping points to the existence of a diffuse and varied, but nonetheless significant information gathering culture among local officials. There was clearly a desire on the part of these officials to understand their custodial subjects and their crimes, but since there was no consensus about the causes of crime in this period there was no agreement about the types of information that needed to be collected, and record-keeping practices varied.

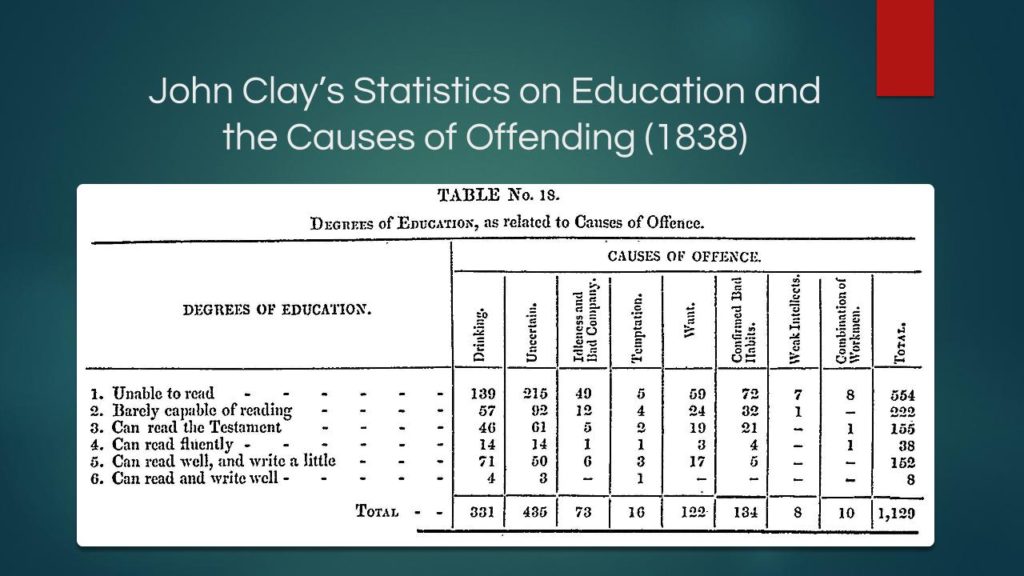

John Clay’s Statistics on Education and Offending

Above is John Clay’s table associating degrees of education with various causes of crime, including drinking, idleness, poverty, etc. Not being able to read is associated with idleness and ‘confirmed bad habits’ (whatever that means), while being able to read and write is associated with drinking as a cause of crime (a warning we should all perhaps heed).

Rather than merely an example of the growth of state power, innovations in criminal record keeping in the nineteenth century reflect a growing desire among those responsible for dealing with crime at the local level to understand their subjects, and to develop new methods of preventing crime and new methods of reforming offenders.

![]()