This post describes a project that myself and a colleague from the Architecture department at the University of Liverpool, Dr Nick Webb, are currently working on–Building Bentham’s Panopticon– which is creating a 3D model of the Panopticon prison viewed through virtual reality software, Oculus Rift.

Bentham’s Panopticon was imagined as the ‘ideal’ prison; it was designed as a circular building with prisoners’ cells arranged around the outer wall and dominated by an inspection tower. From the tower the prison inspector would be able to gaze upon the prisoners at all times. The central inspection principle, Bentham argued, would result in ‘morals reformed, health preserved, industry invigorated, instruction diffused, public burdens lightened…all by a simple idea in architecture’ (Bentham, 1787).

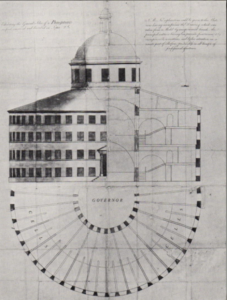

Due to its escalating cost, his designs were never put in to practice. But the recent digitization of Bentham’s plans by Transcribe Bentham, alongside advances in virtual reality software, means that we now have the opportunity to digitally construct the Panopticon and venture inside.

This small element of the wider Digital Panopticon project seeks to explore how we can use digital technology to examine and recreate alternative ways of seeing and experiencing, in a particular space and place-the Panopticon prison- had it been built. Through the use of 3D modelling and virtual reality technology, we can recreate the perspective, positioning and movements- through sight lines, walking routes, and height and weight records- of the gaolers and prisoners who could have potentially been imprisoned within the walls of the Panopticon.

In doing so, this project takes its inspiration from Tim Hitchcock, who is currently modelling the Old Bailey courtroom, and contends that by, ‘building something in three dimensions, with space, physical form and performance, along with new forms of analysis of text; can change how we understand the experience of imprisonment; allow a more fully empathetic engagement with offenders; along with a better understanding of how their experience impacted on the exercise of power and authority’.[1]

Building Bentham’s Panopticon rests upon two lines of enquiry. Firstly, it seeks to rebuild and re-examine the idealized construction of prison discipline at its most ideological- to examine the beginning of the separate, silent system and the development of modern prison reform through architecture. But it also seeks to contribute to a history from below and examine how, by adding in height and weight records of offenders, we can rebuild the perspectives, movements, and thereby explore the potential for transgression that could have occurred within a prison like the Panopticon.

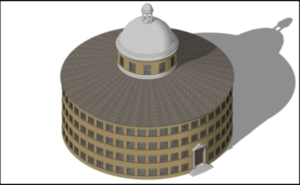

We are about halfway through our research, and are yet to add in biometric data of prisoners taken from the Digital Panopticon project. Yet, in building the model using SketchUp, we have already begun to discover important findings.

The use of 3D modelling has been essential to visualising Bentham’s process and building the interior of the Panopticon. Bentham’s plans, letters and writings about the Panopticon represent a conversation- between himself, architects, managers, and politicians- that include a series of changes to the design of the building and its regime. We are very early on in our findings, but constructing the Panopticon using 3D software, SketchUp, has demonstrated the significance of using this technology to investigate different lines of historical enquiry. Bentham’s never completed the design for the Panopticon, and the debate continued from the 1780s to 1820s. However, plans exist from 1787 and 1791 and these designs are the source from which we have built the 3D models. However, the interior was never fully decided upon due to conflicts between, amongst others, Bentham, John Howard, and William Pitt the Younger.[2]As Nick Webb has argued previously, ‘This is important, as inferences have to be made due to representational source data such as architectural drawings almost always being incomplete’.[3] Therefore, it is necessary to delve in to primary and secondary resources to explore the context, and fill in the gaps in an informed way. For example, Bentham initially wanted the Panopticon to be made out of glass and cast iron. ‘Architecturally’, according to Janet Semple, ‘the Panopticon foreshadows Paxton’s Crystal Palace rather than Pentonville’.[4] However, despite technological innovation in glass manufacture in the late eighteenth century, the building materials were never decided upon, so Nick and I decided to use London stock brick as this was the most commonly used material in London at the close of the eighteenth century.

The models take the form of an idealised, architectural plan, and our current focus is to examine how a series of changes and compromises in the design, seen through the application of 3D modelling, demonstrate the political ideas behind the introduction of the separate, silent system and solitary confinement, but also the relative positions and viewpoints of the different historical actors, in this case, the gaoler, chaplain, and inmates.

What currently interests us at the moment is lines of vision and mobilities as, for Bentham and Foucault, panopticism as a principle is about the power of the gaze- of observation, regulation and power. But I would argue that Foucault and Bentham both had simplistic arguments when it comes to this aspect. In terms of sight lines, or what people can see when stood or walking through a particular point in space, this study builds upon the work of Philip Steadman (UCL). Steadman sketched out two dimensional axonometric drawings of the Panopticon, but with the use of 3D, we are able to build the interior of the Panopticon and therefore provide a space in which the viewer can walk around the prison and inhabit the potential routes of the gaolers, chaplain, and offenders. Steadman draws upon architectural research to plot the totality of what can be seen from a fixed position- also known as an ‘isovist’. (Steadman, 2012: 16).

In Steadman’s image here, you’ll see that the shaded area shows the warder’s isovist. The warder must circulate continuously to watch all the prisoners on his floor. But Steadman’s method, while highlighting the problems in Bentham’s design, is set from a fixed point. Our study builds on this in two crucial ways: firstly, we are able, through the use of Oculus Rift and Virtual Reality Software, to recreate the viewpoints and sight perspective of the gaoler, chaplain, visitors, and offenders, and secondly, we are able to move beyond fixed isovist points to follow the potential mobilities of both gaoler and offender had they been incarcerated in the Panopticon.

So Bentham designed the process of observation to be one way; that is, that the governor, gaolers, other prison staff, and prison visitors to be able to observe the convicts, but that the convicts could only look upon the inspectors gallery. This was, in essence, the central inspection principle. The idea was that every prisoner should be under constant apprehension that he might be observed, night and day, even if no-one was actually looking in his direction at that very moment. He would thus be constantly fearful of being discovered in any misdemeanour.

The Panopticon was a disciplinary technique for making a new social individual; a social laboratory where new subjects were made. Under Bentham’s design, the inmate doesn’t know when they are being watched, and assumes that they are under surveillance at any time. Therefore the prisoner is the subject of observation and power – and this is power through observation. By learning to internalize system of discipline, to watch himself or herself, the Panopticon, theoretically at least, aimed to produce reform through the regulation of the self. The aim of this kind of discipline was, according to Foucault, to turn inmates into quiet, orderly, tractable, malleable subjects or what he provocatively calls ‘Docile Bodies’. As Foucault stated, ‘solitude is the primary condition of total submission’ (Foucault, 1975: 237). Each individual, in his place, is securely confined to a cell from which he is seen from the front by the supervisor; but the side walls prevent him from coming into contact with his companions.

He is seen, but he does not see; he is the object of information, never a subject in communication (Foucault, 1975: 201).The prisoner is therefore, the object of power rather than an agent of power – ‘the object of information’ – never a ‘subject in communication’.

And it is this very notion- the power of the gaze and the power relations that manifest through looking- that Building Bentham’s Panopticon seeks to investigate. The use of 3D and Virtual Reality technology, allows us to put Foucault’s theory, and Bentham’s designs, to the test.

NB Please note that the models are incomplete at present, so may contain errors and inconsistencies.

[1] T. Hitchcock, ‘Voices of Authority: Towards a history from below in patchwork’,

https://blog.digitalpanopticon.org/?cat=25 [Accessed 22 April 2016].

[2] J. Semple (1993),

Bentham’s Prison: A Study of the Panopticon Penitentiary (Oxford University Press: Oxford).

[3] N. Webb & A. Brown (2016). Digital re-analysis of lost architecture and the particular case of Lutyens׳ Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral. Frontiers of Architectural Research.

[4] J. Semple (1993),

Bentham’s Prison: A Study of the Panopticon Penitentiary (Oxford University Press: Oxford), pp. 116-117.